Mongolians were so famous in the 13th-14th centuries that its glory still persisted in the 15th- 16th century, despite its internal turmoil, even in Tibetan plateau.

By the 14th century, Mongolian Empire grew so much that it was hard to maintain the political order. Hence, many self-declared khans, besides those widely accepted, were emerging in different parts of the empire. One of whom was Altan Khan.

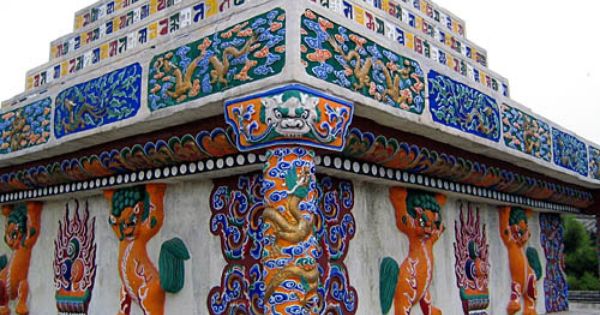

“In the mid-sixteenth century, Altan Khan of the Tumed tribe on the south of the Gobi carried out a military campaign in Tibetan territory and re-established intimate ties between Mongolia and Tibet.”* Such intimate ties meant a marriage between Tibetan religious leaders and Mongolian political/military leaders. On the one hand, Tibetans needed military back-up to protect them from external threats and, on the other hand, Mongolian political leaders needed soft power, namely religious doctrine, to soften the hard power which was going out of control in their homeland.

Altan Khan held a couple of high-level meetings with the Tibetan religious leaders in the late 1500s. During one of those meetings, he bestowed a title to the Tibetan religious master ‘Dalai’ which can be translated as oceanic, meaning supreme and vast. In return, the Tibetan master conferred Altai Khan a title which he could use to prove his supremacy and international acceptance to people back home.

According to Glenn Mullin, “The Dalai Lama incarnation lineage was not, of course, known by the name “Dalai” at the time. Rather, both at home and abroad he was known as Jey Tamchey Khyenpa, or “The Omniscient Master.” The Third carried the ordination name of Sonam Gyatso. When he arrived in Hohhot, the then southern capital of Mongolia, the king Altan Khan translated the “Gyatso” part of his name in Mongolian. Thus Gyatso became Dalai, and Jey Tamchey Khyenpa became “The Dalai Lama Dorjechang.”**

As mentioned earlier, Mongolia did not have very friendly and warm relations with Tibet during Genghis Khan’s time. Because Tangut leaders did not keep their words to Genghis Khan, he made taking revenge on Tangut his life’s goal. In fact, Genghis Khan’s very last battle was with Tangut in which “the Great Khan ordered the execution of the entire Tangut royal family as punishment for their defiance.”***

Ironically, Tangut or Tibet became Mongolia’s “best friend” centuries later. According to different sources, Mongolian khans travelled all the way to Tibetan plateau in search for religious or spiritual guidance because their closer neighbors like Chinese had very different lifestyle, and thus, mentality from Mongols. Yet, Tibetans had a lot in common with Mongols at the time; cultural similarity and common religious practices were among the top on the list.

The most notable outcome of Mongolia’s love-hate relationship with Tibet is its adoption of Tibetan Buddhism which is still a dominant religion in Mongolia. In the multilateral environment, the fact that Dalai Lama is a Mongolian title bestowed by a Mongolian king to the Tibetan religious leader, centuries ago, might strike many.